Cells’ recycling system plays a surprising role in shaping immune cell DNA

Researchers have discovered a new mechanism by which B cells – antibody-producing immune cells – use a cellular recycling process called autophagy to control changes to their DNA essential for antibody improvement. The findings could have future implications for the development of certain blood cancers and autoimmune diseases. The new study, published in The Journal for Clinical Investigation, was led by scientists at Barts Cancer Institute (BCI), Queen Mary University of London.

B cells are crucial immune cells that produce antibodies – molecules capable of recognising and binding foreign elements, enabling our immune system to mount an attack. When B cells encounter the same threat, they fine-tune their antibodies by a process called somatic hypermutation. In this process, the DNA responsible for antibody production rapidly accumulates random variations. These healthy mutations gradually enhance the antibodies’ ability to bind their targets.

However, if this mutation process malfunctions, it can cause uncontrolled, harmful mutations at random sites throughout the genome, potentially disrupting essential genes. This dysregulation may contribute to autoimmune diseases and blood cancers. The mechanisms cells use to control somatic hypermutation, and why it sometimes fails, remain incompletely understood.

Researchers at Barts Cancer Institute, led by Professor Andrejs Braun, Dr Tanya Klymenko and Dr Marta Crespi Sallan, have been investigating the role of a protein called Lamin B1, which forms part of the nuclear envelope surrounding a cell's DNA.

"We observed a striking correlation: autophagy proteins increased as Lamin B1 decreased. That's where everything began."

— Dr Marta Crespi Sallan

"Lamin B1 is what we term a mutational gatekeeper," explains Professor Braun. "It helps shape the nucleus and influences gene expression. When Lamin B1 is depleted, nuclear DNA becomes exposed and more prone to damage."

Therefore, understanding how B cells control their Lamin B1 levels is key to deciphering how lymphoma and other diseases involving dysregulated B cell function develop.

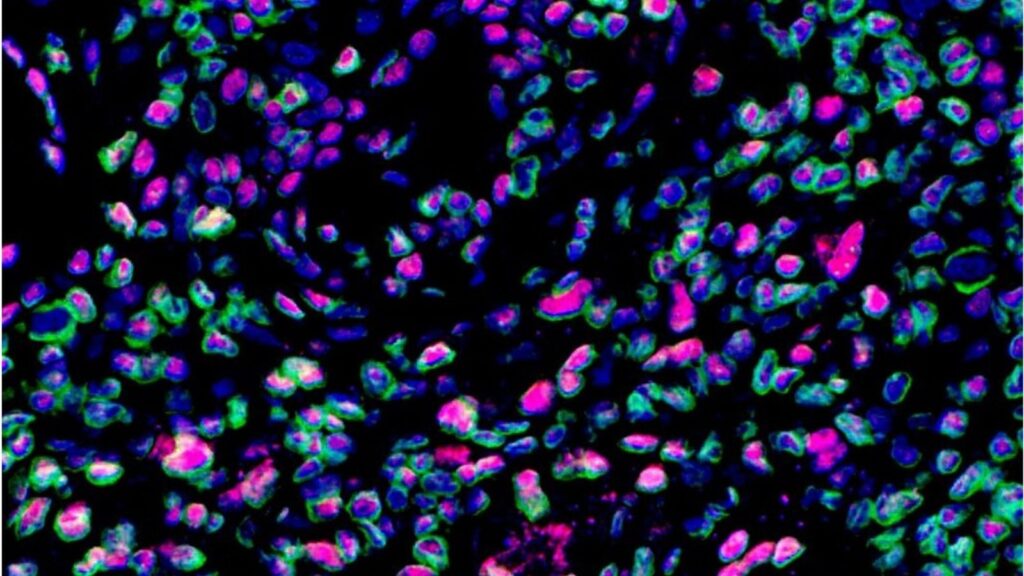

The researchers focused on a process called autophagy – a recycling system that cells use to digest and repurpose their own components. They studied specialised structures in human tissue called germinal centres, where B cells refine their antibodies to fight infections. "We observed a striking correlation: autophagy proteins increased as Lamin B1 decreased. That's where everything began," Dr Crespi Sallan notes.

The team found that B cells use autophagy to dismantle Lamin B1. This breakdown was essential for increasing DNA accessibility, allowing the necessary mutations for antibody refinement to occur. These findings challenge the conventional view of autophagy as merely a general waste-disposal system. Instead, they reveal that cells employ autophagy as a precise tool to selectively remove nuclear components and regulate critical genomic functions.

"Our findings demonstrate that autophagy naturally shapes the immune response by regulating B cell adaptation and function in both health and disease."

— Dr Andrejs Braun

Intriguingly, the researchers also observed this newly identified pathway active in tissue samples from people with Sjögren’s syndrome, an autoimmune disease associated with an increased risk of lymphoma. "Our findings demonstrate that autophagy naturally shapes the immune response by regulating B cell adaptation and function in both health and disease," Dr Braun says.

Moving forward, the team will explore whether targeting the autophagy-Lamin B1 pathway could benefit patients with autoimmune diseases or blood cancers. They plan to investigate its influence on B cell lymphoma development and its interactions with other cellular processes. Ultimately, a deeper understanding of Lamin B1's role might enable its use as a biomarker in blood cancers to aid diagnosis, predict progression, monitor disease activity, and guide personalised treatment.

This work was made possible by collaboration with Queen Mary's William Harvey Research Institute, with Dr Elena Pontarini and Professor Michele Bombardieri providing key expertise in autoimmunity and Sjögren’s Syndrome.

The study was funded by Blood Cancer UK and Cancer Research UK.

Category: General News, Publications

No comments yet